The Role of the Nominated Signatory

It is worth reminding yourself of the history which led to the inception of our current medicines laws and regulations, the intention behind them, and the importance of the Nominated Signatory role.

Your role is to protect patients by making sure we only promote our medicines within the terms of the marketing authorisation and that our marketing is not misleading.

Nowadays laws governing medicines promotion usually include two key criteria for the information provided in materials. It must:

- be consistent with approved product information; and

- not be deceptive or inaccurate.

Most countries also have many additional requirements governing promotion of medicines that are laid out in various codes and guidelines, however, most are details driving the above fundamental requirements and others support two other core principles:

- that clinicians should not be inappropriately influenced in their prescribing; and

- that we need to respect the serious nature of medicine in the way we operate.

All four principles are to protect patients.

Consider these examples which illustrate how patient safety has been compromised in the past:

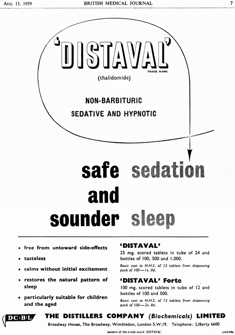

The Thalidomide Disaster

The first paper describing the pharmacological effects of thalidomide was published in 1936. It was the only non-‐barbiturate sedative available at that time. It entered the German market in 1957 as an over-‐the-‐counter sedative that was ‘particularly suitable for infants and the elderly’. It was advertised as ‘safe’ and ‘free from untoward side effects’.

It was soon discovered that thalidomide could also relieve morning sickness in pregnant women although this was an unlicensed indication. By 1960, thalidomide was marketed in 46 countries, with sales nearly matching those of aspirin. Notably it was refused a licence in the US due to lack of clinical evidence about its side effects. By 1960 doctors had expressed concerns over its teratogenic effects – in particular severe limb deformities in babies born to mothers who had taken it during pregnancy. It was withdrawn in 1961 after which the regulations were changed to ensure that any new drug was screened for the potential to cause harm to the unborn baby.

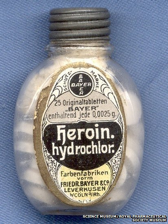

Advertising of heroin (diamorphine)

Diacetylmorphine (diamorphine) was first synthesized in 1874 by Charles Romley Alder Wright, an English chemist. He had been experimenting with combining morphine with various acids and produced a more potent, acetylated form of morphine.

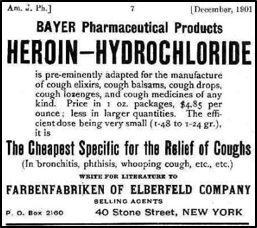

From 1898 through to 1910, diacetylmorphine was marketed by Bayer under the trade-‐name ‘Heroin’ as a non-‐addictive alternative to morphine and cough suppressant. By 1899, Bayer was producing about a ton of heroin a year, and exporting the drug to 23 countries. There were heroin pastilles, heroin cough lozenges, heroin tablets, water-‐soluble heroin salts and a heroin elixir in a glycerine solution.

"It possesses many advantages over morphine," wrote the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal in 1900. "It's not hypnotic, and there's no danger of acquiring a habit.”

In 1913, Bayer decided to stop making heroin when its addictive properties were recognized. There had been an explosion of heroin related hospital admissions in the US and a large population of recreational users was reported. The next year the use of heroin without prescription was outlawed in the US. (A court ruling in 1919 made it illegal for doctors to prescribe it to addicts.)

Heroin was first restricted in the UK in 1868 due to 'unprofitable diversion of workers' and an international ban followed after the first World War.

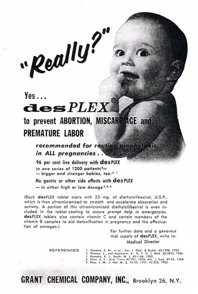

The diethylstilbestrol (DES) story

In the 1940s, the synthetic oestrogen, diethylstilbestrol (DES), was advertised around the world to “prevent miscarriages” and in healthy pregnancies “to make babies stronger”.

The advert shown here states that it was recommended for routine prophylaxis in ALL pregnancies, and that it had ‘no gastric or other side effects’.

Unfortunately women who took it ended up with a higher risk of breast cancer and their daughters, exposed in utero, developed reproductive tract abnormalities and, in some cases, a rare form of vaginal cancer.